When Hype Fails: Are Cannabis Giants Like Canopy and Tilray Just Ponzi Schemes in Disguise?

TORONTO-There’s an old saying in finance: “If you don’t understand where the returns are coming from, you might be the return.” While actual Ponzi schemes are illegal frauds—where old investors are paid with new investors’ money rather than from real profits—some public companies walk a fine line. They may not be fraudulent, but they operate with a similar vibe: endless hype, perpetual losses, and survival through dilution rather than performance.

Nowhere is this dynamic more visible than in the cannabis sector. Once hailed as the next great green rush, the industry has instead become a case study in investor disillusionment—especially when it comes to former titans like Canopy Growth Corporation (CGC) and Tilray Brands (TLRY).

Let’s dig into why some cannabis companies, while not Ponzi schemes by definition, carry all the hallmarks of one in investor experience.

What’s a Ponzi Scheme—Really?

At its core, a Ponzi scheme is a scam. It involves paying earlier investors with money from newer ones, rather than through legitimate profits. The entire system is built on deception and collapses the moment new capital stops flowing.

But not all financial disappointments are illegal. Sometimes companies can look like they’re running a Ponzi scheme—not because they’re fraudulent, but because their survival depends on a constant influx of investor capital with no sustainable business model underneath.

Enter: the cannabis sector.

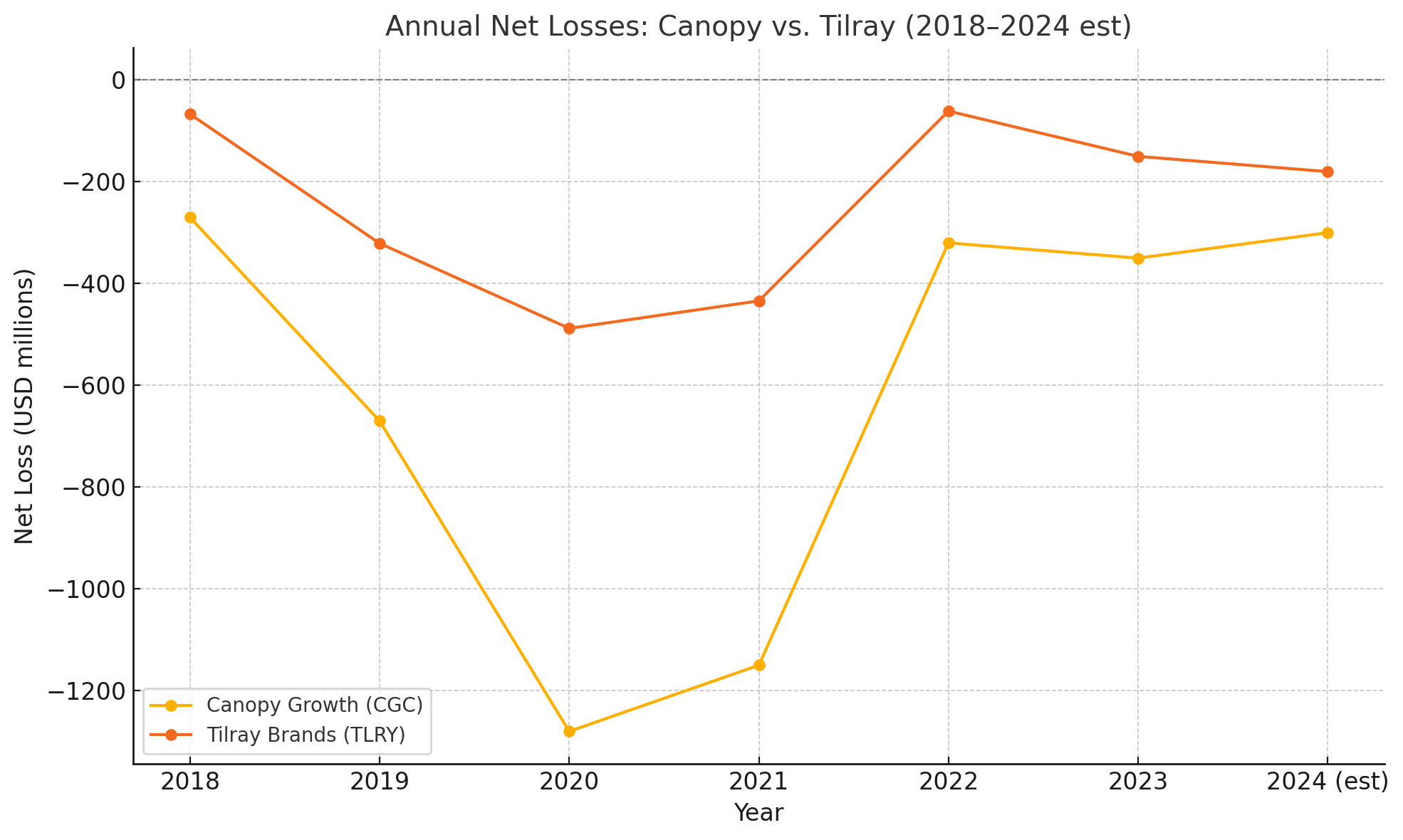

The Rise and Stall of Canopy Growth

Once the golden child of global cannabis, Canopy Growth drew billions in capital, including a blockbuster investment from Constellation Brands. The narrative was strong: international expansion, a first-mover advantage, and a runway to dominate recreational and medical cannabis.

But the reality?

-

Canopy has never posted consistent profits.

-

It’s burned through cash and assets like wildfire.

-

Multiple restructurings, executive shakeups, and impairments have gutted long-term investor confidence.

-

And yet, it keeps raising capital—mostly through share dilution, not performance.

So why do investors keep coming back? Because the story changes just enough to keep hope alive: now it’s U.S. expansion via a “Canopy USA” structure. Before that, it was Canadian dominance. Before that, European medical markets.

Ponzi-like? In feel, yes. But not illegal. Everything’s disclosed, and investors should know better. Still, the fact remains: old shareholders get diluted, new ones buy into a dream that has yet to come true, and the company limps forward—more zombie than juggernaut.

Tilray: From IPO Darling to M&A Drifter

Tilray became a household name in 2018 during its epic IPO run—briefly soaring from $20 to over $200. It was the poster child for cannabis mania. But like all hype bubbles, it popped.

Today, Tilray is:

-

Still unprofitable, despite multiple pivots.

-

Stretching into alcohol and wellness products—acquiring craft breweries and CBD companies to offset weak cannabis margins.

-

Sustained largely by stock-based deals and equity raises, not strong earnings or organic growth.

And here’s the kicker: shareholders keep getting diluted to fund M&A, despite no clear evidence that these deals will drive profitability. It’s an echo of the Ponzi playbook: raise, acquire, spin the story, repeat.

Why It Feels Like a Ponzi—But Isn’t

Both Canopy and Tilray exhibit similar traits to Ponzi schemes:

-

They rely on fresh investor money to stay afloat, via share dilution.

-

They promise future growth without ever delivering sustained profit.

-

They pivot constantly, chasing new markets or narratives to stay relevant.

-

Retail investors get hurt, while insiders and early movers often exit first.

But here’s the legal and structural difference: they disclose everything. These aren’t frauds. They’re speculative companies that were built for a regulatory future that hasn’t arrived. Investors aren’t being lied to—they’re just betting on dreams rather than earnings.

The Cannabis Sector’s Fundamental Problem

What makes cannabis particularly prone to this dynamic?

-

Regulatory gridlock: The U.S. remains federally illegal. Banking, taxes (280E), and market fragmentation make profitability incredibly difficult.

-

Overcapitalization: The sector raised far more than it could responsibly deploy, building empires without demand.

-

Retail investor mania: The legalization narrative brought in meme stock energy—FOMO-driven capital without due diligence.

Together, this created a petri dish for companies that live on promises, not profits.

So What’s the Investor Takeaway?

Companies like Canopy and Tilray aren’t Ponzi schemes in the legal sense—but for many investors, the outcome feels uncomfortably similar. You invest on a dream. They raise more money. The dream changes. Your stake gets diluted. The company survives another quarter. Rinse and repeat.

It’s not illegal. It’s just bad business wrapped in good storytelling.

As the cannabis sector matures—and regulation (hopefully) catches up—these models will need to evolve or vanish. In the meantime, investors should demand more than hype and hope. In cannabis, as in finance, “high potential” without real performance isn’t worth the paper it’s printed on.